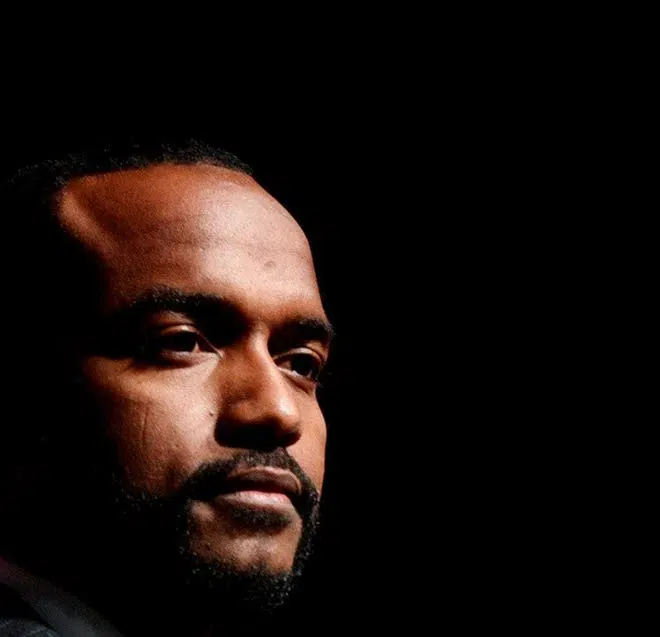

Adrian Perkins still remembers the feeling of not having enough.

How it feels to gargle water dashed with salt and pepper instead of visiting a doctor for a sore throat. How his feet would dangle from the chairs in the building where his mother worked a second job cleaning offices after he finished school. If she wasn’t working another job, she was attending night classes, and her busy schedule meant little time for help with homework or planned meals.

“We had ‘wish sandwiches.’ Just a piece of bread, and you’d wish you had some meat on it,” Perkins said with a chuckle.

But Perkins also remembers what the extra income from his mother’s second job — and later a second marriage — provided for their family. She was eventually able to buy a car, which allowed Perkins to stay at school later. He used that flexibility to become captain of the track team and class president, accolades he parlayed into a West Point nomination.

Now Perkins is the mayor of his hometown of Shreveport, La., an accomplishment he sees as an example of how financial security can change the narrative in a parish that, like so many Southern counties, has seen poverty rates over 20% for three decades.

It’s an experience he’s drawing on as one of five Southern mayors — along with Steve Benjamin in Columbia, S.C., Chokwe Antar Lumumba in Jackson, Miss., Keisha Lance Bottoms in Atlanta, and LaToya Cantrell in New Orleans — who this year agreed to support local guaranteed income programs, a potential solution to cyclical poverty in a region where inequalities have long been entrenched.

“I understand the working poor and what they’re going through,” Perkins said. “If you’re working 40 hours a week, you’re doing what you’re supposed to do to take care of your family. The fact that you’re not making enough money to survive, that’s not your fault. That’s a fundamental flaw in the economy.”

INTERUPT THE CYCLE OF POVERTY

Guaranteed income is a monthly, no-strings-attached cash payment intended to provide financial stability for those who don’t earn enough to meet basic needs.

The efforts by Lumumba, Perkins, Benjamin, Bottoms and Cantrell are supported by the Mayors for Guaranteed Income coalition — a national coalition of 25 mayors founded by Mayor Michael Tubbs of Stockton, Calif. In part, it’s a response to mounting social and economic unrest caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The experimental programs will be funded mostly with private capital.

In 1967, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. touted guaranteed income as “the most effective” method of eradicating poverty. The civil rights leader called it a “moral obligation” of the nation.

“The curse of poverty has no justification in our age,” King wrote in his 1967 book “Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?”.

More than 50 years later, King’s theory will finally be tested in some of the states where he fought injustices.

Benjamin, the first of the five to reveal a city-led guaranteed income program plan, said the city will use private donations to pay 100 families $500 a month for a year starting at the end of the year.

Specifically, the city will select families from the north side of Columbia, an area Benjamin said has led the state in heart disease and diabetes as well as incarceration.

“What we’re seeing is all these issues are completely interconnected,” Benjamin said. “Families who suffer from intergenerational poverty there, they need an interrupter right now. They need thoughtful and creative ways to interrupt the cycle of poverty.”

Perkins has not released additional details about his plan but said, once implemented, he hopes the money will provide peace to mothers like his, who would have benefited from more support.

“It would have opened a lot of options for her,” Perkins said. “It would have given her precious time to spend with her children.”

The national economy is often spoken of as an engine, a powerful machine that will go further faster as long as citizens keep filling the tank with currency.

Combating local-level poverty isn’t seen so simply, and often, poverty reforms focus more on support services through housing or education and less on direct measures for income security.

In the capital of Mississippi, the state with the highest poverty rate in the nation (19.7%), Lumumba hopes the discussion of guaranteed income will reframe poverty as a human concern, rather than an economic one.

“People aren’t fighting for access to capital. They’re fighting for access to live,” Lumumba said. “We’ve done everything for poor people except give them money.”

THE FIGHT AGAINST SOUTHERN POVERTY

The South is not alone in trying to alleviate income inequality.

Guaranteed income programs are being tested and piloted in other parts of the country. The goal of the Mayors for Guaranteed Income pilot program is to use private funding to give low-income citizens cash stipends, no strings attached. The hope is that positive results from a pilot could shape future state and federal policies.

“The key questions we’re looking at are: ‘What are the outcomes we anticipate it will impact’ and ‘Who is it for?’” said Stacia Martin-West, an assistant professor of the University of Tennessee’s College of Social Work who is responsible for analyzing the results of the Mayors for Guaranteed Income pilot programs.

While all the cities have stories to tell of racial and income inequalities, the participation of Perkins, Benjamin, Lumumba, Bottoms and Cantrell is significant for a region uniquely plagued by economic inequality.

Poverty has declined nationwide since King called for its eradication. But the Southern region, as defined by the U.S. Census, continues to lead the nation in poverty rate (9.3%) just as it did in 1967.

Of the 460 counties nationwide that have endured over 20% poverty for three decades, 49% are in the South, according to the Congressional Research Service. The top 15 lowest median income states includes seven Southern states, according to the U.S. Census.

From 2017-18, at a time when left-leaning coastal cities began exploring the concept of guaranteed income, the South was the only region in the U.S. to show zero decline in poverty rate.

“I was like, ‘Yeah, New York and San Francisco are going to do it, but until we get to the American South, we’re not having the conversation we need to have around poverty, racism, sexism and the systemic issues that keep people from achieving upward mobility,’” Martin-West said.

WILL IT WORK?

Now that those conversations are taking place, the next step is determining the efficacy of the programs and addressing skepticism about its use. Will they work? How will people spend the money? Will it decrease the labor force?

Martin-West said results have been consistent, though the sample size for guaranteed income research is small within the American economy. For example, she points to the casino dividend for the North Carolina’s Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and the Seattle-Denver Income Maintenance Experiment of the 1960s.

“By and large, what we saw from those experiments is no appreciable impact on employment. What we do see are really positive impacts around health, around education, around stress and wellbeing,” Martin-West said.

In Jackson, Miss., Lumumba has had a front-row seat to the potential of guaranteed income since December 2018.

That’s when the Magnolia Mother’s Trust began giving $1,000 a month to Black, low-income mothers living in government subsidized affordable housing.

Aisha Nyandoro, CEO of Springboard to Opportunities, which manages the program, said they weren’t seeing residents moving out of the affordable housing communities at a desired rate. Nyandoro sat down with residents to ask what would help.

“Time and time again we heard families say they needed cash,” Nyandoro said.

Since then, the program has expanded from 20 mothers to 110. Some used the money to help purchase a home of their own. Others paid down predatory lending debt. In the first year, the number of women who could pay their bills without additional support grew from 37% to 80%, Nyandoro said.

Some mothers were able to go back to school or spend more time making meals for their family. The unrestricted income didn’t just change the narrative; it provided the agency for women to tell their own stories, Nyandoro said.

“Really we just saw individuals for the first time having the breathing room to sit down and actually plan for their immediate needs but also the future,” Nyandoro said. “Cash allows you the ability to actually plan and that’s what a lot of us take for granted.”

Proponents of the program say guaranteed income is not meant to be a silver bullet. Apart from the individual benefits a family will receive, the pilot programs will increase the amount of data that can be used to create community-driven poverty solutions.

“So often elected officials are so afraid of doing the wrong thing, that they don’t do anything. When it comes to poverty in America, we can be guilty as a country of admiring the problem. Sometimes you have to think bigger, try harder and see what results you can get for your people,” Benjamin said.

Decades before Benjamin began working to implement guaranteed income in Columbia, King was prepared to bring the idea there himself.

King had been scheduled to appear at a rally at Columbia’s Zion Baptist Church on April 3, 1968, according to a newspaper report published days earlier in The Columbia Record. And while it’s unknown if King was going to speak, the article mentioned his Poor People’s Campaign and ongoing fight to pressure the federal government to adequately address poverty. King altered his schedule to return to Memphis and support the sanitation workers’ strike instead. He was assassinated on April 4 that year.

By testing guaranteed income, Benjamin hopes to see King’s dream come to life.

“This ties directly to Dr. King’s legacy and I’m proud to try to bring a little life to it.”

Comments