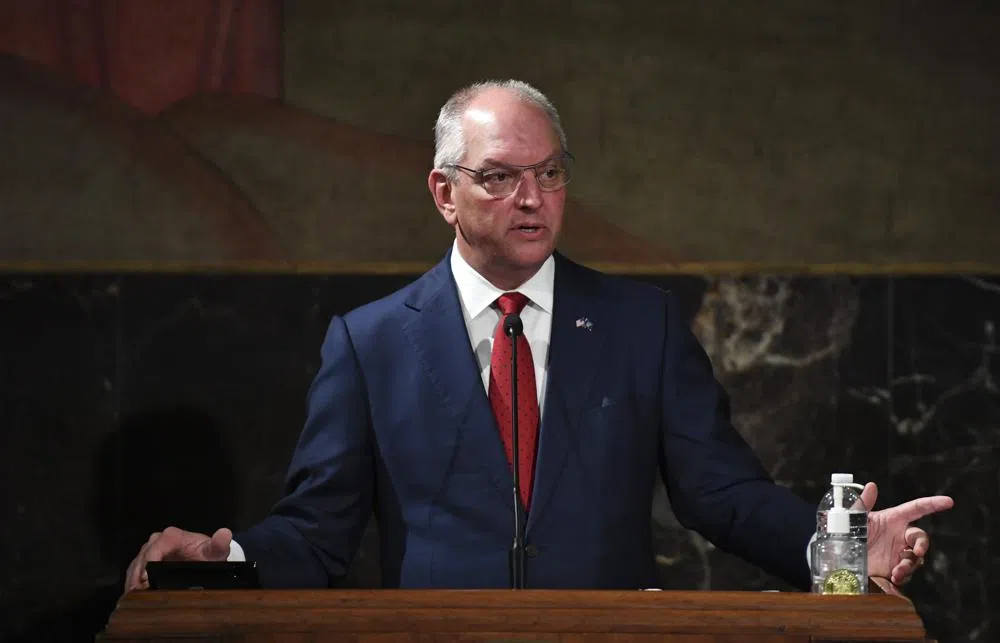

BATON ROUGE, La. (AP) — Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards, a Democrat in a deep-red state, was immersed in a difficult reelection campaign when he received a text message from the head of the state police: Troopers had engaged in “a violent, lengthy struggle” with a Black motorist, ending with the man’s death.

Edwards was notified of the circumstances of Ronald Greene’s death within hours of his May 2019 arrest, according to text messages The Associated Press obtained through a public records request. Yet the governor kept quiet as police told a much different story to the victim’s family and in official reports: that Greene died from a crash following a high-speed chase.

For two years, Edwards remained publicly tight-lipped about the contradictory accounts and possible cover-up until the AP obtained and published long-withheld body-camera footage showing what really happened: white troopers jolting Greene with stun guns, punching him in the face and dragging him by his ankle shackles as he pleaded for mercy and wailed, “I’m your brother! I’m scared! I’m scared!”

The governor has rebuffed repeated interview requests and his spokesperson would not say what steps, if any, Edwards took in the immediate aftermath of Greene’s death. “The governor does not direct disciplinary or criminal investigations,” said spokesperson Christina Stephens, “nor would it be appropriate for him to do so.”

What the governor knew, when he knew it and what he did have become questions in a federal civil rights investigation of the deadly encounter and whether police brass obstructed justice to protect the troopers who arrested Greene.

“The question is: When did he find out the truth?” said Sen. Cleo Fields, a Baton Rouge Democrat who is vice-chair of a legislative committee created last year to dig into complaints of excessive force by state police.

The FBI has questioned people in recent months about Edwards’ awareness of various aspects of the case, according to law enforcement officials who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss the probe. Investigators have focused in part on an influential lawmaker saying the governor downplayed the need for a legislative inquiry.

The governor’s spokesperson said he is not under investigation and neither is any member of his staff.

Edwards kept quiet about the Greene case through his reelection campaign in 2019 and through a summer of protests in 2020 over racial injustice in the wake of George Floyd’s killing. Even after Greene’s family filed a wrongful-death lawsuit that brought attention to the case in late 2020, Edwards declined to characterize the actions of the troopers and refused calls to release their body-camera video, citing his concern for not interfering with the federal investigation.

But when the AP obtained and published the long-withheld footage of the encounter that left Greene bloody, motionless and limp on a dark road near Monroe, Edwards finally spoke out.

Edwards condemned the troopers, calling their actions “deeply unprofessional and incredibly disturbing.”

“I am disappointed in them and in any officer who stood by and did not intervene,” the governor said in a statement. He later called the troopers’ actions “criminal.”

But Edwards, a lawyer from a long family line of Louisiana sheriffs, also has made comments since the release of the video that downplay troopers’ actions, even reprising the narrative that Greene may have been killed by a car crash.

“Did he die from injuries sustained in the accident?” Edwards said in response to a question on a radio show in September. “Obviously he didn’t die in the accident itself because he was still alive when the troopers were engaging with him. But what was the cause of death? I don’t know that that was falsely portrayed.”

Weeks after those remarks, a reexamined autopsy commissioned by the FBI rejected the crash theory outright, attributing Greene’s death to “physical struggle,” troopers repeatedly stunning him, striking him in the head, restraining him at length and Greene’s use of cocaine.

The federal investigators have taken interest in a conversation Edwards had last June with state Rep. Clay Schexnayder, the powerful Republican House speaker who was considering a legislative inquiry into the Greene case following the release of the video.

Schexnayder said this week that the governor told him there was no need for further action from the legislature because “Greene died in a wreck.” The speaker said he never moved forward with the investigation to avoid interfering with the federal probe.

The governor’s spokesperson acknowledged he briefed the legislative leadership on his “understanding of the Greene investigation” and said his remarks were consistent with his public statements. The U.S. Department of Justice declined to comment.

“It’s time to find out what happened, who knew what and when, and if anyone has covered it up,” Schexnayder told the AP. “The Greene family deserves to know the truth.”

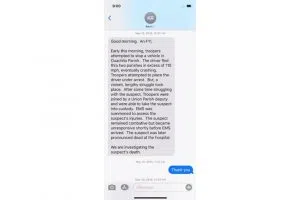

Edwards received word of the Greene case in a text from then-Louisiana State Police Superintendent Kevin Reeves on May 10, 2019, at 10 a.m., about nine hours after the deadly arrest.

Edwards received word of the Greene case in a text from then-Louisiana State Police Superintendent Kevin Reeves on May 10, 2019, at 10 a.m., about nine hours after the deadly arrest.

“Good morning. An FYI,” the message read. “Early this morning, troopers attempted to stop a vehicle in Ouachita Parish. The driver fled thru two parishes in excess of 110 mph, eventually crashing. Troopers attempted to place the driver under arrest. But, a violent, lengthy struggle took place. After some time struggling with the suspect, troopers were joined by a Union Parish deputy and were able to take the suspect into custody. … The suspect remained combative but became unresponsive shortly before EMS arrived.”

The explanation given to Edwards, which his spokesperson called a “standard notification,” was far different from what Greene’s family says it was being told by troopers at almost the same time — that the 49-year-old died on impact in a car crash at the end of a chase. A coroner’s report that day indicates Greene was killed in a motor vehicle accident and a state police crash report makes no mention of troopers using force.

Reeves ended his text by telling the governor that the man’s death was under investigation.

“Thank you,” Edwards responded.

Those words were among the few statements from Edwards himself released in response to an extensive public-records request the AP filed in June for materials relating to Greene’s death. The governor’s office has not released any messages from Edwards to his staff and has yet to fully respond to a separate December request for his texts with three top police officials.

Hundreds of other emails and text messages released by the governor’s office show that while he has publicly distanced himself from the case and issues of state police violence, his staff has been more engaged behind the scenes, including his top lawyer repeatedly contacting state and federal prosecutors about the Greene case.

Alexander Van Hook, who until December oversaw the civil rights investigation into Greene’s death as the acting U.S. attorney in Shreveport, said in November there has been no attempt by the governor to influence the investigation. “That wouldn’t go over very well with us if there had been,” Van Hook told AP.

Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry, a Republican, said Edwards had a duty to at least follow up with the head of the state police after being informed of Greene’s death.

“When something goes wrong … he’s shocked,” Landry said, ”when behind the scenes he is intimately involved in trying to control the message and distort it from the public.”

Meanwhile, state police recently acknowledged that the department “sanitized” the cellphone of Reeves, intentionally erasing messages after he abruptly retired in 2020 amid AP’s initial reporting on Greene’s death. The agency said it did the same to the phone of another former police commander, Mike Noel, who resigned from a regulatory post last year as he was set to be questioned about the case by lawmakers. Police said such erasures are policy.

Edwards’ office said the governor first learned of the “allegations surrounding Mr. Greene’s death” in September 2020 — the same month in which a state senator sent Edwards’ lawyers a copy of the Greene family’s wrongful-death lawsuit that had been filed a few months earlier.

No one has yet been charged with a crime in Greene’s death and only one of the troopers involved in his arrest has been fired. Master Trooper Chris Hollingsworth, who was recorded saying he “beat the ever-living f— out of” Greene, died in a car crash in 2020 soon after learning he would lose his job.

In early October 2020, after AP published audio of Hollingsworth’s comments, the governor reviewed video of Greene’s fatal arrest, his spokesperson said.

Some observers of Edwards’ response to the Greene case see it as partly political calculation. At the time of the deadly arrest, the centrist Democrat was in a tough reelection campaign in a deeply conservative state against a Republican backed by Donald Trump. His path to reelection depended on high Black turnout and crossover support from law enforcement

Greene’s death — and the footage that ultimately went viral — would have “politically threatened both voting groups simultaneously,” said Joshua Stockley, a political scientist at the University of Louisiana Monroe.

But the first public indications that Greene had been abused did not emerge until months after Edwards eked out 51% of the vote over businessman Eddie Rispone. He won in large part due to massive turnout by Black voters in urban areas, taking 90% of the vote in Orleans Parish, the 60% Black parish that includes New Orleans.

“I find it hard to believe that the release of this video during the election would not have had a profound consequence,” Stockley said. “It would have been enormous.”

Comments